Hello. This is the second thread of the writefag circle, here: >>299458 →

Basically all that is said in that OP applies to this one but I'll go through the 'rules' of this thread here as well.

So, the main point of this thread is to facilitate and enable Anons' writefagging; in a similar way pride facilitates and enables aids.;^P The Anons in this thread can be seperated into two camps: Anons who wants help with their writing project(s) and Anons that feel inclined to help those aforementioned shrek-colored skinheads.

Crafting and beta-reading is what we do here, any critique of literature not made by a guy submitted for this thread should be incidental; it should be when you —as a beta-reader of fics posted ITT— make a comparision between the fic your reviewing and some other story for the sake of demonstrating your point, whatever it is.

This is NOT: A review thread for unsolicited rants about random media which does not fall into the mold for how to use a refrence in this thread described in the above paragraph. Meaning if you're not using —like, let's pick something arbitrary— Naruto for a comparision in your critique of someone's writing itt, then don't bring it up. I understand that tangents can happen and if it's like a few exchanges with a pair of posters; then it's fine. However, don't make this a pattern and also move whatever off-thread-topic discussion to a more fitting board/thread. There's after all no problem with finding someone to converse with and share perspectives on a subject you care about but just take it to an appropriate thread. Sidenote: Nigel, these rules applies to you in a stricter fashion because I would not have to detail them with this much precision if it weren't for you.

I hope that I haven't scared anybody off. This is still suppose to be a chill af thread. Funposting is very much allowed and encouraged. It really is more that some type of posting —like, things that are completely irrelevant to the thread— does not belong here. I know, rocket-science and a rule that is seldom seen and highly unique for this thread. Perhaps you could call it a... Novelty. (You) intelligent lurker, obviously get the subtext of this OP so you probably won't need to worry about any of this. I'd say if you're unsure if what you're about to post belongs in the thread, then post it anyway. The worst that can happen is that someone tells you to move it to another thread and you get a better insight of what post belongs in thread. If you consist on fish and chips, however, I'd sugguest you think twice on what you're posting and perhaps even ask beforehand if your rant about lefties and Undertale belongs here.

If there are any questions on the OP, ask away?

/mlpol/ - My Little Politics

Archived thread

>>336928

After the last threads trainwreck into the septic tank I think it's time to look for another alternative to the moderation that sits with their thumb on their ass over the Niggel neverending invasion of posts. I think it's worth trying a writefag thread on nhnb but it'll have to be poni only, the OP isn't enough to deter Niggel's dysfunctional brain so why put up with it.

After the last threads trainwreck into the septic tank I think it's time to look for another alternative to the moderation that sits with their thumb on their ass over the Niggel neverending invasion of posts. I think it's worth trying a writefag thread on nhnb but it'll have to be poni only, the OP isn't enough to deter Niggel's dysfunctional brain so why put up with it.

>>336955

Naughty Hoers Neuron Bay? I second this motion. Get ready to have your particles accelerated with the power of piracy!

Also: fuck Niggel, but doublefuck the do-nothing shits that are still defending his pigshit insane retardation.

Naughty Hoers Neuron Bay? I second this motion. Get ready to have your particles accelerated with the power of piracy!

Also: fuck Niggel, but doublefuck the do-nothing shits that are still defending his pigshit insane retardation.

>>336928

Thank you for posting this, I guess Ill start things off then.

One thing to openly declare is, all of my writings lately have been dramatizations of RP events, tyoically Ashes Town. For clarity, this is because whatnis happening in Ashes town is a canon sequence of events that pertain to a DnD campaign Inhave going.

RP event dramatization is a really good venue and impetus to practoce writing, because the difficulty is in making otherwise banal sequences of events into a fleshed-out series of interactions and dialogue. It alsonhelpsbthat the skeleton (what happened) is already formed, and it is only on the authornto describe the interveneing events and minutiae that turn the story from a series of basic exchanges and dice rolls into a coherent storyline.

One can readily differentiate between shitty content and decent content by how many people like hearing the short-hand version of the story, often sparing the author and readers unnecessary effort, and with enough 'approved' content, they can be steung together into a narrative story.

Example from last night:

>What happened

Addy, sitting alone in the bar doing shots. Some rando runs up and steals her drink, drinks it, and starts screaming obscenities. Addy pulls a .500mag, taps him on the forehead with it and (attack roll 94, defense roll 51) kills him.

>Story

Whether with a lead-in from a previous episode of scavenging, or as a stand-alone start to a narrative, I would start by describing the sounds of the bar, the ache of her joints, perhaps the grime on her clothes (possibly referencing previous experiences) and specifically her desire for ease after a hard day.

If a stand-alone, she would reflect on the day and anything significant, before getting a good 2 sheets to the wind. It was a bit of a.celebration (it was a good day) after all.

And then the antagonist would be introduced, first audibly (she could hear him making his way....) and would probably describe her getting focibly pushed aside as he stumbled/pushed/fell past her, taking her drink.

She would then be described as trying to be reasonablr, until he downed the entire bottle and then started hoofing his crotch and spouting the sorts of things Ziggers typically say (with possible references to undesirable ziggers she had dealt with who didnt warrant an episode).

She would then let her rage and alcohol get the better of her, and deciding not to miss in spite of her diminished coordination, would place the barrel against the face for good measure.

The rest of the scene would be pensive. Everypony in the bar had the good sense to ignore the scene (no one responded irl, but it makes a good scene), as she unceremoniously dragged the body - some nopony she had ever seen - outside to skin, clean, and trim, before carrying the remains back to her hideout where she had a natural (powerless) refrigerator buried to preserve meat with.

As she did so, she would think to herself (especially as she sobered) about how she shouldnt have responded so rashly (and indeed, the next morning she would purchase a stout piece of 2x4 for non-lethally disciplining undesirables) but she also knew her friends would have a mighty feast because of this pony's transgressions.

Id end the scene with some sort of affirmation that Addy is neither good nor evil, and that such considerations rarely bothered her, they were just part of living in the wasteland.

Thank you for posting this, I guess Ill start things off then.

One thing to openly declare is, all of my writings lately have been dramatizations of RP events, tyoically Ashes Town. For clarity, this is because whatnis happening in Ashes town is a canon sequence of events that pertain to a DnD campaign Inhave going.

RP event dramatization is a really good venue and impetus to practoce writing, because the difficulty is in making otherwise banal sequences of events into a fleshed-out series of interactions and dialogue. It alsonhelpsbthat the skeleton (what happened) is already formed, and it is only on the authornto describe the interveneing events and minutiae that turn the story from a series of basic exchanges and dice rolls into a coherent storyline.

One can readily differentiate between shitty content and decent content by how many people like hearing the short-hand version of the story, often sparing the author and readers unnecessary effort, and with enough 'approved' content, they can be steung together into a narrative story.

Example from last night:

>What happened

Addy, sitting alone in the bar doing shots. Some rando runs up and steals her drink, drinks it, and starts screaming obscenities. Addy pulls a .500mag, taps him on the forehead with it and (attack roll 94, defense roll 51) kills him.

>Story

Whether with a lead-in from a previous episode of scavenging, or as a stand-alone start to a narrative, I would start by describing the sounds of the bar, the ache of her joints, perhaps the grime on her clothes (possibly referencing previous experiences) and specifically her desire for ease after a hard day.

If a stand-alone, she would reflect on the day and anything significant, before getting a good 2 sheets to the wind. It was a bit of a.celebration (it was a good day) after all.

And then the antagonist would be introduced, first audibly (she could hear him making his way....) and would probably describe her getting focibly pushed aside as he stumbled/pushed/fell past her, taking her drink.

She would then be described as trying to be reasonablr, until he downed the entire bottle and then started hoofing his crotch and spouting the sorts of things Ziggers typically say (with possible references to undesirable ziggers she had dealt with who didnt warrant an episode).

She would then let her rage and alcohol get the better of her, and deciding not to miss in spite of her diminished coordination, would place the barrel against the face for good measure.

The rest of the scene would be pensive. Everypony in the bar had the good sense to ignore the scene (no one responded irl, but it makes a good scene), as she unceremoniously dragged the body - some nopony she had ever seen - outside to skin, clean, and trim, before carrying the remains back to her hideout where she had a natural (powerless) refrigerator buried to preserve meat with.

As she did so, she would think to herself (especially as she sobered) about how she shouldnt have responded so rashly (and indeed, the next morning she would purchase a stout piece of 2x4 for non-lethally disciplining undesirables) but she also knew her friends would have a mighty feast because of this pony's transgressions.

Id end the scene with some sort of affirmation that Addy is neither good nor evil, and that such considerations rarely bothered her, they were just part of living in the wasteland.

>>336964

>Sonata crosses the border to the human dimension, mindrapes the natives, and likes tacos.

What did Hasbro mean by this?

>Sonata crosses the border to the human dimension, mindrapes the natives, and likes tacos.

What did Hasbro mean by this?

1646550601.webm (2.8 MB, Resolution:640x640 Length:00:00:29, 1646546413979(2).webm) [play once] [loop]

So let's kickoff some writing with a simple shitpost.

>Be Anon.

>Be in Rarity's boutique.

>What kinda shenanigans will go down here?

>Oh ho ho.

"Mmmh, this tea is simply divine, Miss rarity," you say as you sip on your green tea.

>Sip sip sip.

>"Oh, isn't it darling. You're such a gentlecolt, Anon. I can only imagine how many mares wishes you were their special somepony." Rarity says and takes miniscule nibble on small diet cookie.

>Rarity's words echo in your head as your teeth grinds together.

>You slap the tea cup off the table so it shatters on the floor.

"But men are suppose to be dominant, not gentle!"

>"Hoooo!" Rarity brings a hoof to her forehead.

"Not posh, but raw and dirty." You grab a chocolate cake, smash it into your face, and start to just smear it over your face.

>Rarity brings her hooves to her chest. leans back, and says, "Oh my."

"Ura ura ura," your deep, croaking laughter surrounds Rarity

>She can't help but to tremble in place.

"M-mister A-Anonymous?" she squeaks out.

"SILENCE!" You slam your fist into the table and a symphony of scrambling porcelain go off.

>You extend you arm, your finger across the table; you dive forth and boop the rarity; Objection!

>You loom over her and the shadow you cast eclipses the sun.

>He eyes widen; "Habububaba habububaba," escapes through her smattering lips.

>Drawing a circle in the air with your finger, you move it from boop-position to having your finger underneath her chin.

"YouuuUUUuuu should know your place, you horse."

>A waterfall of liquid flattens her her stylish velvet curls to her face.

>Behind her stand Pinkie emptying a bottle of lemonad over Rarity.

"Fwoosh!" says Pinkie.

>Be Anon.

>Be in Rarity's boutique.

>What kinda shenanigans will go down here?

>Oh ho ho.

"Mmmh, this tea is simply divine, Miss rarity," you say as you sip on your green tea.

>Sip sip sip.

>"Oh, isn't it darling. You're such a gentlecolt, Anon. I can only imagine how many mares wishes you were their special somepony." Rarity says and takes miniscule nibble on small diet cookie.

>Rarity's words echo in your head as your teeth grinds together.

>You slap the tea cup off the table so it shatters on the floor.

"But men are suppose to be dominant, not gentle!"

>"Hoooo!" Rarity brings a hoof to her forehead.

"Not posh, but raw and dirty." You grab a chocolate cake, smash it into your face, and start to just smear it over your face.

>Rarity brings her hooves to her chest. leans back, and says, "Oh my."

"Ura ura ura," your deep, croaking laughter surrounds Rarity

>She can't help but to tremble in place.

"M-mister A-Anonymous?" she squeaks out.

"SILENCE!" You slam your fist into the table and a symphony of scrambling porcelain go off.

>You extend you arm, your finger across the table; you dive forth and boop the rarity; Objection!

>You loom over her and the shadow you cast eclipses the sun.

>He eyes widen; "Habububaba habububaba," escapes through her smattering lips.

>Drawing a circle in the air with your finger, you move it from boop-position to having your finger underneath her chin.

"YouuuUUUuuu should know your place, you horse."

>A waterfall of liquid flattens her her stylish velvet curls to her face.

>Behind her stand Pinkie emptying a bottle of lemonad over Rarity.

"Fwoosh!" says Pinkie.

So, to whom it may concern;

Ive been working on another episode of Ashes Town adventures, and I was wondering if anyone was interested/willing to read it and give me some feedback. Preferred: less emphasis on what is done well, and more emphasis on what needs improvement.

Im finished with the REALLY rough draft (comparable to my previously posted episode) but I'm re-drafting it to accomplish a variety of editorial and positional goals.

I just wanted to ask for objections before I dump a wall-of-text and demand accommodation.

Ive been working on another episode of Ashes Town adventures, and I was wondering if anyone was interested/willing to read it and give me some feedback. Preferred: less emphasis on what is done well, and more emphasis on what needs improvement.

Im finished with the REALLY rough draft (comparable to my previously posted episode) but I'm re-drafting it to accomplish a variety of editorial and positional goals.

I just wanted to ask for objections before I dump a wall-of-text and demand accommodation.

>>338287

>before I dump a wall-of-text and demand accommodation.

Walls-of-texts of stories are always welcome. No, need to ask permission, even if it was sweet of you.

>before I dump a wall-of-text and demand accommodation.

Walls-of-texts of stories are always welcome. No, need to ask permission, even if it was sweet of you.

>>338288

Appreciated. Just displaying for *ahem* certain audience members how to not alienate the audience in advance. ^_~

Appreciated. Just displaying for *ahem* certain audience members how to not alienate the audience in advance. ^_~

>>338200

Assuming you're the same Sven I've written reviews for in the past, I remember mostly hammering you on ESL issues and dialogue, and this shows marked improvement in both areas. The language here is much less clunky, and the narration is easier to follow than what I've read from you in the past. The dialogue is much more expressive and natural. I actually remember noticing this with the last thing I saw you post as well (don't remember exactly what it was, and I don't think I commented, but I distinctly remember noticing that your English had improved).

That said, I notice you still have a couple of minor issues with verbs:

>I can only imagine how many mares wishes you were their special somepony.

How many mares wish you were their special somepony.

>Rarity's words echo in your head as your teeth grinds together.

Your teeth grind together.

>You slam your fist into the table and a symphony of scrambling porcelain go off.

A symphony goes off.

Also, this line:

>You grab a chocolate cake, smash it into your face, and start to just smear it over your face.

The word "face" is used twice in rapid succession; this kind of redundancy is usually not a good idea. Better to just say "You smash it into your face, and smear it all around" or something to that effect.

>"YouuuUUUuuu should know your place, you horse."

I like the double entendre here.

All in all, this is pretty good. Nice job.

Assuming you're the same Sven I've written reviews for in the past, I remember mostly hammering you on ESL issues and dialogue, and this shows marked improvement in both areas. The language here is much less clunky, and the narration is easier to follow than what I've read from you in the past. The dialogue is much more expressive and natural. I actually remember noticing this with the last thing I saw you post as well (don't remember exactly what it was, and I don't think I commented, but I distinctly remember noticing that your English had improved).

That said, I notice you still have a couple of minor issues with verbs:

>I can only imagine how many mares wishes you were their special somepony.

How many mares wish you were their special somepony.

>Rarity's words echo in your head as your teeth grinds together.

Your teeth grind together.

>You slam your fist into the table and a symphony of scrambling porcelain go off.

A symphony goes off.

Also, this line:

>You grab a chocolate cake, smash it into your face, and start to just smear it over your face.

The word "face" is used twice in rapid succession; this kind of redundancy is usually not a good idea. Better to just say "You smash it into your face, and smear it all around" or something to that effect.

>"YouuuUUUuuu should know your place, you horse."

I like the double entendre here.

All in all, this is pretty good. Nice job.

>>338380

Wow, thanks for the review. Most appreciated.

>I remember mostly hammering you on ESL issues and dialogue

Yes, you did comment a lot about my ESL issues because they have always been a weak point of mine. I even feel bad about having you review some of the stuff I requested since I was so lazy and didn't proofread nor improved between the works I submitted to you.

I don't think you hammered me on dialogue, though, you have even given me props for naturally sounding dialogue on multiple occasions. Maybe your confusing it with something else? You have commented on my narration in the past on matters excluding ESL issues.

Also, my dialogue can certainly have improved as well, I'm not saying that's not possible, but I distinctly remember you giving my credit for my dialogue in the past.

Thanks, again.

Wow, thanks for the review. Most appreciated.

>I remember mostly hammering you on ESL issues and dialogue

Yes, you did comment a lot about my ESL issues because they have always been a weak point of mine. I even feel bad about having you review some of the stuff I requested since I was so lazy and didn't proofread nor improved between the works I submitted to you.

I don't think you hammered me on dialogue, though, you have even given me props for naturally sounding dialogue on multiple occasions. Maybe your confusing it with something else? You have commented on my narration in the past on matters excluding ESL issues.

Also, my dialogue can certainly have improved as well, I'm not saying that's not possible, but I distinctly remember you giving my credit for my dialogue in the past.

Thanks, again.

>>336928

Anyponer have any advice for a writefag that hasn't written anything in a long time and is looking to get back into the swing of things?

Anyponer have any advice for a writefag that hasn't written anything in a long time and is looking to get back into the swing of things?

>>338530

Start writing. But first do yoy know what kind of writer you are?

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLSH_xM-KC3Zv-79sVZTTj-YA6IAqh8qeQ

Start writing. But first do yoy know what kind of writer you are?

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLSH_xM-KC3Zv-79sVZTTj-YA6IAqh8qeQ

>>338560

>Guess you should take a look at the playlist if you have the time

Definitely will, Gonna take awhile though.

>Guess you should take a look at the playlist if you have the time

Definitely will, Gonna take awhile though.

I want to join the book club if anyone sets it up.

1647557079.jpg (97.0 KB, 560x473, Screenshot_20220309-191921_Chrome.jpg)

Many moons had passed since the incidents surrounding Anne #289. Adeline had found a serivceable niche in the commerce market and had carved out a sustainable situation for herself, having achieved a degree of autonomy from the standard vendors. Autonomy affords individual growth, and so she committed herself to developing her situation in Equestria for as long as she should find herself here. This Equestria, that is, which bears not the least resemblance to the Equestria she had heard of. That place was supposed to be nice. This one.... Anyway, the most recent biological pony subject Addy interacted with was 3000 something, causing her to decide to shift gears. The episodes that lead to this perspective shift are too short to di individually, so Ill micro compile them. For now, she has the means and the wont to take all the wayward ponies she finds, giving them a gun, filling their bellies, and setting them on course in the stable or under her own wing if they seem apt (none so far, though she gives free lessons for melee and cqb).

Im planning a periodic diary-esque section in between significant episodes, since the final narration will only describe the details of what happens, and will not display a bias toward the protagonist or any other character. Much of what is detailed in this foreword is to compensate for the hours of effort and detail that WILL go into explaining all these details through story rather than overt explanation.

In a/the finished product, I would not utilize an omniscient narrator, thats just lazy writing. Omniscient narrators are only acceptable when describing otherwise uncorrelated things, so that the nuance of how an apparently spontaneous effect is still possible, predictably; with exception, the protagonist is experiencing a stream of stimulus/context and responding sincerely to it. The waterfall at the end of Oh Brother Where Art Thou wouldnt have made sense without the omniscient narrator, mostly.

Tl;dr Addy's met alot of former 'subjects', bio experiments, slaves (sex and labor), and plain orphans. She prefers to get em safe, get em fed, get em armed, and if needs be, get em trained.

---

It had been a good day of scavenging. She hadn't done a tally, but she knew there were at least 3 dozen assorted fruits and who knows how many bags of caps she'd accumulated. More than a day's work and in just a few hours.

And so she found herself outside the Chipped Hoof, her red mane secured in a high ponytail for simplicity of looking clients and vendors in the eye; also better for killing, not that any of that was expected.

Her armored metal plates, crudely riveted and fastened to her uniform (its self basically a kevlar onesie, but more utilitarian) glistened not at all as she sat in the snow while perpetually smoking a cigarette; her eyes methodically shifting to maintain a her awareness of all the dozens of ponies assembled to either hawk or pick up (through purchase OR theft) goods and merchandise.

Her warm fillyfren sat silently at her side, adopting the alternate direction, side-spooning maneuver particularly popular amongst the fillies. All things considered, it had been a fine day and she was looking forward to relaxing and taking it easy the rest of the day. Until she noticed the approach of a fearful and VERY out-of-place filly.

It wasnt her age that pegged her as out of place, it was her clothes and her expression; a mix of fear and uncertainty you only see on ponies when theyve never been in the wasteland before. She wore a black bandanna and a violet jacket, but these looked clean and new, virtually spotless and untouched by the wasteland. She wasnt alone, in front of her was one of those obnoxious pony-droids being led by two ponies in black tactical gear, the lead of which had a 50mm cannon harnessed to him.

She kept an eye on them and observed the leader - a black-maned stallion is all that could be made of him - issue a series of instructions to the droid. He gestured toward the filly, who visibly diminished when his attention was on her, and crumpled in on herself in a display of absolute defeat. His instructions seemingly issued, he nodded to the other pony, a pink-maned mare so tac'd up that her body-color couldnt be determined. She nodded in response and they turned to head off toward the west (Addy's left). In their absence the robot and the filly,... just fucking stood there. For like a half an hour! Not a word nor sound was uttered between them, only the filly's eyes darted every possible direction, and occasionally looking adversarially at the robot.

Addy exhaled the last of her cigarette and wandered in the direction of the pair. They were fairly close, maybe 40' past a small fire some ponies had made to ward off the chill. Addy deposited her cigarette butt in the fire and sauntered over, about 10' from the pair, closer to the filly than the robot. Both had seen her walk over, but her body language and direction were deliberate to imply that her approach was not related to them.

She maintained this space for a bit, occasionally calling out some of her products (guns/ammo, melee weapons, medical supplies, and TP) and conversing with the occasional passers-by, but still the filly and the robot did nothing.

<Ay,... ay there miss? Scuse me miss? Can I ask ye a question?

Addy spoke to the filly, who went wide-eyed and rigid at the sound.

"Uhm... okay." The filly's discomfort was palatable, and the robot had not seemed to notice the start of the exchange. Addy leaned slightly closer.

Im planning a periodic diary-esque section in between significant episodes, since the final narration will only describe the details of what happens, and will not display a bias toward the protagonist or any other character. Much of what is detailed in this foreword is to compensate for the hours of effort and detail that WILL go into explaining all these details through story rather than overt explanation.

In a/the finished product, I would not utilize an omniscient narrator, thats just lazy writing. Omniscient narrators are only acceptable when describing otherwise uncorrelated things, so that the nuance of how an apparently spontaneous effect is still possible, predictably; with exception, the protagonist is experiencing a stream of stimulus/context and responding sincerely to it. The waterfall at the end of Oh Brother Where Art Thou wouldnt have made sense without the omniscient narrator, mostly.

Tl;dr Addy's met alot of former 'subjects', bio experiments, slaves (sex and labor), and plain orphans. She prefers to get em safe, get em fed, get em armed, and if needs be, get em trained.

---

It had been a good day of scavenging. She hadn't done a tally, but she knew there were at least 3 dozen assorted fruits and who knows how many bags of caps she'd accumulated. More than a day's work and in just a few hours.

And so she found herself outside the Chipped Hoof, her red mane secured in a high ponytail for simplicity of looking clients and vendors in the eye; also better for killing, not that any of that was expected.

Her armored metal plates, crudely riveted and fastened to her uniform (its self basically a kevlar onesie, but more utilitarian) glistened not at all as she sat in the snow while perpetually smoking a cigarette; her eyes methodically shifting to maintain a her awareness of all the dozens of ponies assembled to either hawk or pick up (through purchase OR theft) goods and merchandise.

Her warm fillyfren sat silently at her side, adopting the alternate direction, side-spooning maneuver particularly popular amongst the fillies. All things considered, it had been a fine day and she was looking forward to relaxing and taking it easy the rest of the day. Until she noticed the approach of a fearful and VERY out-of-place filly.

It wasnt her age that pegged her as out of place, it was her clothes and her expression; a mix of fear and uncertainty you only see on ponies when theyve never been in the wasteland before. She wore a black bandanna and a violet jacket, but these looked clean and new, virtually spotless and untouched by the wasteland. She wasnt alone, in front of her was one of those obnoxious pony-droids being led by two ponies in black tactical gear, the lead of which had a 50mm cannon harnessed to him.

She kept an eye on them and observed the leader - a black-maned stallion is all that could be made of him - issue a series of instructions to the droid. He gestured toward the filly, who visibly diminished when his attention was on her, and crumpled in on herself in a display of absolute defeat. His instructions seemingly issued, he nodded to the other pony, a pink-maned mare so tac'd up that her body-color couldnt be determined. She nodded in response and they turned to head off toward the west (Addy's left). In their absence the robot and the filly,... just fucking stood there. For like a half an hour! Not a word nor sound was uttered between them, only the filly's eyes darted every possible direction, and occasionally looking adversarially at the robot.

Addy exhaled the last of her cigarette and wandered in the direction of the pair. They were fairly close, maybe 40' past a small fire some ponies had made to ward off the chill. Addy deposited her cigarette butt in the fire and sauntered over, about 10' from the pair, closer to the filly than the robot. Both had seen her walk over, but her body language and direction were deliberate to imply that her approach was not related to them.

She maintained this space for a bit, occasionally calling out some of her products (guns/ammo, melee weapons, medical supplies, and TP) and conversing with the occasional passers-by, but still the filly and the robot did nothing.

<Ay,... ay there miss? Scuse me miss? Can I ask ye a question?

Addy spoke to the filly, who went wide-eyed and rigid at the sound.

"Uhm... okay." The filly's discomfort was palatable, and the robot had not seemed to notice the start of the exchange. Addy leaned slightly closer.

>>338678

<Is everythin alright with ye? Are ye safe? Yer not in danger are ye?

She couldnt avoid making side-glances at the robot, and the filly caught on as she looked directly at the robot before turning back to respond.

"I... I don't... know," she stammered out, appearing on the verge of tears.

<Calm down lass. Do ye need a weapon? Ah kin give ye one fer defense. Is jus' a wee 9mm, but whatever ye're wrapped up in

is what she had been saying, except the robot had now noticed the exchange, its awareness seemingly drawn to the presence of the hoofgun.

"Possible threat detected" it droned emotionlessly, its optical sensors scanning her in a half-dozen ways.

"Leave this area at once." it again droned.

<Ah'll go whur a wunt, a when a wunt, mate

she said, flicking the remainder of a cigarette at the robot's head though narrowly missing. She then turned directly toward the filly and urged

<The gun, take it. Ah git the feelin yer gonna need it afore long

The robot however opened a large compartment on its flank and out sprung what to the naked eye appeared to be an RPG mounted to an armiture, that levelled on Addy with a distinct chunk as its servos locked on target.

"Preparing to fire. Subject is to get immediately behind this unit in 10 seconds."

The filly was the first to respond, literally leaping to motion and cowering behind the robot with her hooves over her head. Addy was the second to move running right up to the robot and placing her face in front of the unsent grenade.

<Go ahead mate, at this range its sure to make a mess of us both!

she challenged, subtly thinking to herself that her abilities would heal these wounds, and most assuredly disable the robot.

She wasnt so lucky however, and doubly so. The robot did not fire, thankfully, it held its position; from behind Addy however - unnoticed because of the exchange - came the sound of a very large cannon, specifically the 50mm she had seen earlier. Without flinching or turning her head, from her peripheral Addy could barely make out the pink-maned mare at her left flank, a laser pistol clenched in their mouth and pointed in her direction.

"Report!" that previously mentioned lead-pony barked from behind Addy.

"Unit stationed and functioning as ordered. Currently on standby engaging a hostile...

<Ah aint hostile!

... target attempting to sell weapons to the subject.

<An ah aint the one brandishin' explosive ordinance!

She suddenly sprung toward the ground to break their line of fire, and with a slight tumbling maneuver sprung toward the leader. Once upright, her head ducked quickly down and firmly clamped the head of a fragmentation grenade just inside her lapel. As she drew it out fully, she caught the ring with her right 'hoof' and pulled. Barely anyone had registered, and Addy was now positioned face to face with this leader-pony, only Addy had an active grenade in her mouth, and was the only thing preventing it from going off.

<Ah guess that puts us on equal footin' dunnit?

She slightly slurred as her mouth clutched the grenade.

<Is everythin alright with ye? Are ye safe? Yer not in danger are ye?

She couldnt avoid making side-glances at the robot, and the filly caught on as she looked directly at the robot before turning back to respond.

"I... I don't... know," she stammered out, appearing on the verge of tears.

<Calm down lass. Do ye need a weapon? Ah kin give ye one fer defense. Is jus' a wee 9mm, but whatever ye're wrapped up in

is what she had been saying, except the robot had now noticed the exchange, its awareness seemingly drawn to the presence of the hoofgun.

"Possible threat detected" it droned emotionlessly, its optical sensors scanning her in a half-dozen ways.

"Leave this area at once." it again droned.

<Ah'll go whur a wunt, a when a wunt, mate

she said, flicking the remainder of a cigarette at the robot's head though narrowly missing. She then turned directly toward the filly and urged

<The gun, take it. Ah git the feelin yer gonna need it afore long

The robot however opened a large compartment on its flank and out sprung what to the naked eye appeared to be an RPG mounted to an armiture, that levelled on Addy with a distinct chunk as its servos locked on target.

"Preparing to fire. Subject is to get immediately behind this unit in 10 seconds."

The filly was the first to respond, literally leaping to motion and cowering behind the robot with her hooves over her head. Addy was the second to move running right up to the robot and placing her face in front of the unsent grenade.

<Go ahead mate, at this range its sure to make a mess of us both!

she challenged, subtly thinking to herself that her abilities would heal these wounds, and most assuredly disable the robot.

She wasnt so lucky however, and doubly so. The robot did not fire, thankfully, it held its position; from behind Addy however - unnoticed because of the exchange - came the sound of a very large cannon, specifically the 50mm she had seen earlier. Without flinching or turning her head, from her peripheral Addy could barely make out the pink-maned mare at her left flank, a laser pistol clenched in their mouth and pointed in her direction.

"Report!" that previously mentioned lead-pony barked from behind Addy.

"Unit stationed and functioning as ordered. Currently on standby engaging a hostile...

<Ah aint hostile!

... target attempting to sell weapons to the subject.

<An ah aint the one brandishin' explosive ordinance!

She suddenly sprung toward the ground to break their line of fire, and with a slight tumbling maneuver sprung toward the leader. Once upright, her head ducked quickly down and firmly clamped the head of a fragmentation grenade just inside her lapel. As she drew it out fully, she caught the ring with her right 'hoof' and pulled. Barely anyone had registered, and Addy was now positioned face to face with this leader-pony, only Addy had an active grenade in her mouth, and was the only thing preventing it from going off.

<Ah guess that puts us on equal footin' dunnit?

She slightly slurred as her mouth clutched the grenade.

Thats the 1st half of the episode, Im still working on the second half. The actual dialogue was much shorter, but was organic relative to a game interaction; reiterating and paraphrasing it more fitting for a full social interaction is more difficult than I had anticipated, without making glaring errors or compromising tone. For example, while in game Addy is a 'cowe' (since all characters are quadrupeds), but in the story she is a 1/2 minotaur (ala Iron Will). While she she has humanoid hands, she is a satyr abomination and can as readily walk upright as she can on all 4's. In order to avoid attention/notoriety, she wraps her hands so to more resemble the covered hooves that are the norm. But she only reveals her hands either to ponies she can trust (so shes cooking for them) or to ponies who arent going to survive the encounter (so she's cooking them).

These are all details that have played out in previous episodes, but which influence how this episode is being portrayed.

These are all details that have played out in previous episodes, but which influence how this episode is being portrayed.

Four trails of sparks trailed after the hooves of a mare; her horseshoes glowed yellow as she slid across the cobblestone streets. The hem of her cloak pendulum swung over to the other side when she ground to a halt.

She had appeared around a street corner and stopped in between a demon and the family of ducks.

"Honk! Honk!" the duck quacked, which roughly translated into, "You cracka' ass almost hit me, mutchafucka'. You come in here driftin' but yo' ain't even got a lambo, genowhaahmsayin'?"

The pony did not understand and gently pushed, with her snout, the duck mom away. The mare wanted her to take her ducklings and go.

"Honk! Honk!" Or, "Don't grab mah asss, nigguha! You wan' me to beat yo' ass? Huh? Huh?"

This stubborn duck ain't moving, the mare thought before she turned towards the demon.

It was a jaguar the size of a house with Minotaur hands for front legs. The hairs in its fur disappeared in the blackness of it as if the creature didn't grow fur but void. It opened its maw and a chimney-sized python rolled out between the demon's fangs. "Sssss," came from the snake's air-sawing cloven tongue as its slit eyes focused on the mare.

"Now gooOO0oo!" the mare shouted.

"Honk. Honk. Honk!" A.K.A: "What'cha sayin'? I know you wa'mah swagger up in yo' crib, an'mah crew, biiiii-tch."

A quick glance back told the mare that the mother duck still hadn't moved to safety. The mare sighed and a tree crown of light grew from her horn in a flash. Mother duck and her family of ducklings re-hatched from eggs of magic light on the mare's back.

"Honk!" Or as it's known in the pond kingdom, "Ay ay ay, watch mah kiiids. I need 'em for breadcrumbs, foo!"

She had appeared around a street corner and stopped in between a demon and the family of ducks.

"Honk! Honk!" the duck quacked, which roughly translated into, "You cracka' ass almost hit me, mutchafucka'. You come in here driftin' but yo' ain't even got a lambo, genowhaahmsayin'?"

The pony did not understand and gently pushed, with her snout, the duck mom away. The mare wanted her to take her ducklings and go.

"Honk! Honk!" Or, "Don't grab mah asss, nigguha! You wan' me to beat yo' ass? Huh? Huh?"

This stubborn duck ain't moving, the mare thought before she turned towards the demon.

It was a jaguar the size of a house with Minotaur hands for front legs. The hairs in its fur disappeared in the blackness of it as if the creature didn't grow fur but void. It opened its maw and a chimney-sized python rolled out between the demon's fangs. "Sssss," came from the snake's air-sawing cloven tongue as its slit eyes focused on the mare.

"Now gooOO0oo!" the mare shouted.

"Honk. Honk. Honk!" A.K.A: "What'cha sayin'? I know you wa'mah swagger up in yo' crib, an'mah crew, biiiii-tch."

A quick glance back told the mare that the mother duck still hadn't moved to safety. The mare sighed and a tree crown of light grew from her horn in a flash. Mother duck and her family of ducklings re-hatched from eggs of magic light on the mare's back.

"Honk!" Or as it's known in the pond kingdom, "Ay ay ay, watch mah kiiids. I need 'em for breadcrumbs, foo!"

>>339491

The giant python pulled back its head and like an expert boxer, the mare could predict the future from this alone. With a red flash of her horn, the hem of her cloak rose into the air as if she was mountain-climbing and a gust blew right up from underneath her.

"Honk!" quacked the mother duck and she also said this, "Wow wow wow, what iz this woodoo crap muthafucker. Ain't gonna let no pony popo gonna lock me up."

The hems closed around the ducks like a daytime flower in the evening and with a knot of fabric on top, the ducks were safely boxed in.

"Quack! Honk!" Or, "Ay, wesa'ma rites muthafucka'? I know mah way to the court, I go there every day, what the fuck is theese? There ain't even bum-smellin' weed here, nigguha!"

The python pounced and the mare exploded into a cloud of red sparks. The python grimaced as it swallowed the fire but not from digging up the stones in the road and sending them skipping. The mare reappeared with a pop on the top of a rooftop.

"Honk!" Also, referred to as, "Wah happened? It felt like I was shot again. Sheeeeit, mah phd!"

The two heads of the beast turned towards the sounds. In a concerted effort, the pair swung the snake-tongue up into the air, and then it came crashing down like a whip. Again, the Mare disappeared in a cloud of particles as the snake's body karate chopped the building in two.

Stones lifted like balloons out of the road puzzle and drifted past the demon-beast. As the snake shook its head in an attempt to recover focus, the jaguar's eyes widen as it saw floating stones wrapped in a transparent, red veil. Its pupils darted downwards and found itself standing on a circle of glowing red lines. The jaguar-head twirled around and found the mare standing on the street again. When it saw the mare's horn, it growled and displayed teeth. It blazed with plasma; it shone, it burned, and it dripped liquid that both vaporized the ground and burnt it.

The giant python pulled back its head and like an expert boxer, the mare could predict the future from this alone. With a red flash of her horn, the hem of her cloak rose into the air as if she was mountain-climbing and a gust blew right up from underneath her.

"Honk!" quacked the mother duck and she also said this, "Wow wow wow, what iz this woodoo crap muthafucker. Ain't gonna let no pony popo gonna lock me up."

The hems closed around the ducks like a daytime flower in the evening and with a knot of fabric on top, the ducks were safely boxed in.

"Quack! Honk!" Or, "Ay, wesa'ma rites muthafucka'? I know mah way to the court, I go there every day, what the fuck is theese? There ain't even bum-smellin' weed here, nigguha!"

The python pounced and the mare exploded into a cloud of red sparks. The python grimaced as it swallowed the fire but not from digging up the stones in the road and sending them skipping. The mare reappeared with a pop on the top of a rooftop.

"Honk!" Also, referred to as, "Wah happened? It felt like I was shot again. Sheeeeit, mah phd!"

The two heads of the beast turned towards the sounds. In a concerted effort, the pair swung the snake-tongue up into the air, and then it came crashing down like a whip. Again, the Mare disappeared in a cloud of particles as the snake's body karate chopped the building in two.

Stones lifted like balloons out of the road puzzle and drifted past the demon-beast. As the snake shook its head in an attempt to recover focus, the jaguar's eyes widen as it saw floating stones wrapped in a transparent, red veil. Its pupils darted downwards and found itself standing on a circle of glowing red lines. The jaguar-head twirled around and found the mare standing on the street again. When it saw the mare's horn, it growled and displayed teeth. It blazed with plasma; it shone, it burned, and it dripped liquid that both vaporized the ground and burnt it.

>>339511

The python coiled itself around a building and the jaguar part of the demon used its minotaur hands to grab a tree respectively a lamppost. The mare lowered her head. Sparks flew in arcs from her horn. A vein bulge appeared along her neck as she was struggling to pull her head up again. The duck mom quacked something as the cloth-pack, she and her ducklings wherein, lifted off. More stones followed; the mare's tail rose like a line; and all small, light objects in the area climbed upwards. Due to the dullness and blackness of the giant cat's hairs, it looked more like it burned with pitch-black flames rather than hairs being pulled.

The mare trusted up her horn and in phfff the magic around it dissipated. The demon's back legs were the first to go; they were pulled upwards by some invisible force. A small whirlwind danced around the demon, who remained anchored with his hands and serpent-tongue. The python's grip slipped and in the next moment, it flailed in the air as it pulled the jaguar's head backward. The next thing to go was the hand that held the lamppost. The tree groaned and creaked. Roots breached the ground and became branches. Crack. The demon rocketed into the air as one of its hands carried with it a whole tree.

The mare's gaze followed the demon as it became smaller and smaller. The magic in the area dispersed; her tail and cloak fell back down. When her fabric package fell down, it became undone.

"Honk. Honk!" A.K.A, "Shaniqua! Yo' assssssssssss."

The python coiled itself around a building and the jaguar part of the demon used its minotaur hands to grab a tree respectively a lamppost. The mare lowered her head. Sparks flew in arcs from her horn. A vein bulge appeared along her neck as she was struggling to pull her head up again. The duck mom quacked something as the cloth-pack, she and her ducklings wherein, lifted off. More stones followed; the mare's tail rose like a line; and all small, light objects in the area climbed upwards. Due to the dullness and blackness of the giant cat's hairs, it looked more like it burned with pitch-black flames rather than hairs being pulled.

The mare trusted up her horn and in phfff the magic around it dissipated. The demon's back legs were the first to go; they were pulled upwards by some invisible force. A small whirlwind danced around the demon, who remained anchored with his hands and serpent-tongue. The python's grip slipped and in the next moment, it flailed in the air as it pulled the jaguar's head backward. The next thing to go was the hand that held the lamppost. The tree groaned and creaked. Roots breached the ground and became branches. Crack. The demon rocketed into the air as one of its hands carried with it a whole tree.

The mare's gaze followed the demon as it became smaller and smaller. The magic in the area dispersed; her tail and cloak fell back down. When her fabric package fell down, it became undone.

"Honk. Honk!" A.K.A, "Shaniqua! Yo' assssssssssss."

I feel like I know how to write but I always end up second-guessing myself. How do I end this vicious cycle Mlpol?

>>339862

Literally just keep writing and don't stop, even if it's shit.

You can go back and edit shit content, but you can't fix what was never written.

Literally just keep writing and don't stop, even if it's shit.

You can go back and edit shit content, but you can't fix what was never written.

>>339882

Well, thanks for the advice but I've done that a few times and it never worked before. I need some way of feeling that I progress and that I also don't write shit.

Well, thanks for the advice but I've done that a few times and it never worked before. I need some way of feeling that I progress and that I also don't write shit.

>>339884

>Shit

As in, I want to write something I feel has merits. That's probably why I stop writing things because I can't help but to think about how they seem to lose the point or thread.

>Shit

As in, I want to write something I feel has merits. That's probably why I stop writing things because I can't help but to think about how they seem to lose the point or thread.

>>339884

Well, why don't you select specific reasons as to why you feel your writing is shit and chip away them one piece at a time starting with the more fundamental issues? Rome wasn't built in a day.

I do this while writing new little stories and comparing them to my older trash. It seems to help just a little bit.

I'm having the same problem you are, but I'm not even an ESL fag.

I literally just want to write a silly, erotic shitpost story to annoy a certain subset of the fandom on fimfic. I think my biggest problem is that I only feel like writing when I'm drunk and want to shitpost while ruthlessly praising the virtues of my waifus, much to the chagrin of other spergs that take themselves way too seriously.

Well, why don't you select specific reasons as to why you feel your writing is shit and chip away them one piece at a time starting with the more fundamental issues? Rome wasn't built in a day.

I do this while writing new little stories and comparing them to my older trash. It seems to help just a little bit.

I'm having the same problem you are, but I'm not even an ESL fag.

I literally just want to write a silly, erotic shitpost story to annoy a certain subset of the fandom on fimfic. I think my biggest problem is that I only feel like writing when I'm drunk and want to shitpost while ruthlessly praising the virtues of my waifus, much to the chagrin of other spergs that take themselves way too seriously.

>>339887

This

Nice satan Id trips, btw

>>339885

So, practice with writing that 'doesnt' have merit. Consider taking a banal story and trying to make it interesting through expression. Pick a theme, something you know is boring and uninteresting, and then dial it up. Make that nonsense story/scene as exciting as you can.

This

Nice satan Id trips, btw

>>339885

So, practice with writing that 'doesnt' have merit. Consider taking a banal story and trying to make it interesting through expression. Pick a theme, something you know is boring and uninteresting, and then dial it up. Make that nonsense story/scene as exciting as you can.

>>339882

I appreciate the, 'keep at it' ideal, though, because I won't stop trying.

>>339887

>Rome wasn't built in a day.

And this idea about splitting the problem in to smaller pieces is also good. This makes me think about how I want to concretize my writing process. I really don't like writing something and then dropping it because I found that I either have nowhere to go or because it kinda feels pointless.

How does one plot a story? Because if I had a finished scheme to follow, I would always make progress. I haven't written one of those before. But I think that would be the way forward for me.

>>339888

>Make that nonsense story/scene as exciting as you can.

I don't think I can. It's hard for me to be spontaneously funny like that, idk, maybe it's just some insecurity that hinders me.

If I imagine myself following that advice, I see myself ending up describing the scenery and the characters of the scene in a serious manner and then either turning up the violence, lewdness, or quirky memes. Others on this site do this well and can make it feel fresh. I just kinda hate it when I do it. Also, I kinda feel like sex and edginess is a sign of a story with low substance but I understand that it's about the context in which you put these subject matters that matter, though.

I appreciate the, 'keep at it' ideal, though, because I won't stop trying.

>>339887

>Rome wasn't built in a day.

And this idea about splitting the problem in to smaller pieces is also good. This makes me think about how I want to concretize my writing process. I really don't like writing something and then dropping it because I found that I either have nowhere to go or because it kinda feels pointless.

How does one plot a story? Because if I had a finished scheme to follow, I would always make progress. I haven't written one of those before. But I think that would be the way forward for me.

>>339888

>Make that nonsense story/scene as exciting as you can.

I don't think I can. It's hard for me to be spontaneously funny like that, idk, maybe it's just some insecurity that hinders me.

If I imagine myself following that advice, I see myself ending up describing the scenery and the characters of the scene in a serious manner and then either turning up the violence, lewdness, or quirky memes. Others on this site do this well and can make it feel fresh. I just kinda hate it when I do it. Also, I kinda feel like sex and edginess is a sign of a story with low substance but I understand that it's about the context in which you put these subject matters that matter, though.

>>339884

Writing is a grueling process, but the best answer is to continuously write and re-write.

Another helpful practice is reading. Read the works of other artists to expand your understanding of literary devices and even your vocabulary.

Writing is a grueling process, but the best answer is to continuously write and re-write.

Another helpful practice is reading. Read the works of other artists to expand your understanding of literary devices and even your vocabulary.

>>339895

Literally, a scene with a protag doing the laundry could be expounded into a critique on the fundamental experience/existence of man, and made into a compelling dissertation.

But.

The likelyhood of setting out to write a protag-doing-laundry scene and elegantly transitioning from that into a critique on the fundamental experience/existence of man such that that's what the story is known for is... highly probable, keep at it.

Seriously, do keep at it, but dont kid yourself about it; a great story isnt happenstance or accidental. It takes practice and determination. At least, that seems to be how it goes.

Literally, a scene with a protag doing the laundry could be expounded into a critique on the fundamental experience/existence of man, and made into a compelling dissertation.

But.

The likelyhood of setting out to write a protag-doing-laundry scene and elegantly transitioning from that into a critique on the fundamental experience/existence of man such that that's what the story is known for is... highly probable, keep at it.

Seriously, do keep at it, but dont kid yourself about it; a great story isnt happenstance or accidental. It takes practice and determination. At least, that seems to be how it goes.

>>339895

>How does one plot a story? Because if I had a finished scheme to follow

>scheme

Do...do you mean like, a timeline of events and/or plotpoints or something? I mean, I...I don't pretend to know jackshit about this; everyone here already knows am full of shit. But I...I dunno honestly.

Too long of a shot...

>How does one plot a story? Because if I had a finished scheme to follow

>scheme

Do...do you mean like, a timeline of events and/or plotpoints or something? I mean, I...I don't pretend to know jackshit about this; everyone here already knows am full of shit. But I...I dunno honestly.

Too long of a shot...

1648526251.jpg (71.1 KB, 800x806, sunset-shimmer-twilight-sparkle-my-little-pony-sunny.jpg)

>>339897

I'm grateful for the advice but I don't really like rewriting. It has worked out in the past but only if I feel enthusiastic enough about the text to rewrite it.

So I need to have something that I like to begin with. That's what I struggle to get.

>>339898

I been think about what you say here and the one I replied to above in this post said. It ties into the concept of that dicotomy of either you're a pantser (discovery writing) or plotter (arcitech writing) or whatever (or something in between) that I have seen been talked about before. I'm not sure if this makes sense or not but I do think that I'd like to plot a story before I write it for a change because I'm tired of feeling like I'm just writing random and pointless nonesense while finding my way out of a maze. Sometimes I manage to escape the maze and those times are the stories which I'm proud of.

>>339900

>Do...do you mean like, a timeline of events and/or plotpoints or something?

Yes. I searched for it on the internet, a go-to method I've gotten more into recently, and this is what I found, https://writersedit.com/fiction-writing/ultimate-guide-how-to-write-a-series/

>everyone here already knows am full of shit.

Well, you'll be surprised to learn then that I don't think you're full of shit. Just because your story has serious formatting issues doesn't mean that your ideas need to be bad. I do obviously keep in mind who said what but I also like to examine ideas in isolation from whose idea it is.

>Too long of a shot...

Wha.......? What... is it... that you're... trying to... communicate?

I'm grateful for the advice but I don't really like rewriting. It has worked out in the past but only if I feel enthusiastic enough about the text to rewrite it.

So I need to have something that I like to begin with. That's what I struggle to get.

>>339898

I been think about what you say here and the one I replied to above in this post said. It ties into the concept of that dicotomy of either you're a pantser (discovery writing) or plotter (arcitech writing) or whatever (or something in between) that I have seen been talked about before. I'm not sure if this makes sense or not but I do think that I'd like to plot a story before I write it for a change because I'm tired of feeling like I'm just writing random and pointless nonesense while finding my way out of a maze. Sometimes I manage to escape the maze and those times are the stories which I'm proud of.

>>339900

>Do...do you mean like, a timeline of events and/or plotpoints or something?

Yes. I searched for it on the internet, a go-to method I've gotten more into recently, and this is what I found, https://writersedit.com/fiction-writing/ultimate-guide-how-to-write-a-series/

>everyone here already knows am full of shit.

Well, you'll be surprised to learn then that I don't think you're full of shit. Just because your story has serious formatting issues doesn't mean that your ideas need to be bad. I do obviously keep in mind who said what but I also like to examine ideas in isolation from whose idea it is.

>Too long of a shot...

Wha.......? What... is it... that you're... trying to... communicate?

>>339902

I don't know why i didn't suggested you this, given that you are actually pretty good at executing a story. I guess it's because I wasn't aware of the dichotomy you mentioned.

Anyways, I genuinely think this might turn out pretty well for you, keep at it Svenstein!

>I don't think you're full of shit. Just because your story has serious formatting issues doesn't mean that your ideas need to be bad.

Oh, okay. It's just pretty easy for me to sound like an arrogant dick.

>Wha.......? What... is it... that you're... trying to... communicate?

Nevermind, it's not important.

I don't know why i didn't suggested you this, given that you are actually pretty good at executing a story. I guess it's because I wasn't aware of the dichotomy you mentioned.

Anyways, I genuinely think this might turn out pretty well for you, keep at it Svenstein!

>I don't think you're full of shit. Just because your story has serious formatting issues doesn't mean that your ideas need to be bad.

Oh, okay. It's just pretty easy for me to sound like an arrogant dick.

>Wha.......? What... is it... that you're... trying to... communicate?

Nevermind, it's not important.

Unrelated to Carlos' story, I found this video both compelling and insightful

[YouTube] George Orwell's 4 Tips For Speaking Clearly![]()

[YouTube] George Orwell's 4 Tips For Speaking Clearly

>George Orwell is one of the most celebrated writers of the twentieth century. Most loved and remembered for his fiction, he also produced an expansive array of essays, including "Politics and the English Language", which contains his advice regarding clarity in writing and speaking.

>Today's political and academic landscape is often accused of being rife with rambling unclarity, and this was something Orwell also perceived and lamented in his own time, making much of his advice on how to avoid this still relevant today.

>Today's political and academic landscape is often accused of being rife with rambling unclarity, and this was something Orwell also perceived and lamented in his own time, making much of his advice on how to avoid this still relevant today.

>>339966

>given that you are pretty good at executing a story.

Thanks. I'm a bit curious what gave you that impression? Was it my latest "story" (even if it was more like an action scene without context)? In such a case, I'm glad you liked it. I'm pretty proud of it myself. When I wrote it, I thought about the list of advice on clear and impactful writing that I'd taken in lately (I might post them later). It's funny that Anon here: >>339988 mentioned clarity because that's a lot of what was trying to accomplish with my writing here.

>When it comes to how to write plots

I have been thinking about starting by summarizing the story into one sentence and from there kinda unpack it (Or develop it further).

>given that you are pretty good at executing a story.

Thanks. I'm a bit curious what gave you that impression? Was it my latest "story" (even if it was more like an action scene without context)? In such a case, I'm glad you liked it. I'm pretty proud of it myself. When I wrote it, I thought about the list of advice on clear and impactful writing that I'd taken in lately (I might post them later). It's funny that Anon here: >>339988 mentioned clarity because that's a lot of what was trying to accomplish with my writing here.

>When it comes to how to write plots

I have been thinking about starting by summarizing the story into one sentence and from there kinda unpack it (Or develop it further).

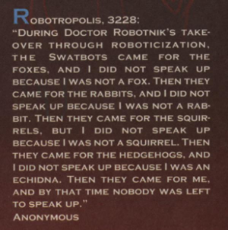

I just found pic in the old thread. I didn't read it thoroughly enough to realize the punchline at the end. Pretty cool Anon who wrote this, if you're still here: Good job.

Though, I don't get the point with the name of the creature.

Though, I don't get the point with the name of the creature.

>>339992

>summarizing the story into one sentence and from there kinda unpack it

Cant support this idea enough. Consider it a mission/thesis statement. Doing so also helps to drive home the essential elements of the story while also emphasizing that anything NOT part of that sentence is optional or outright unnecessary.

>summarizing the story into one sentence and from there kinda unpack it

Cant support this idea enough. Consider it a mission/thesis statement. Doing so also helps to drive home the essential elements of the story while also emphasizing that anything NOT part of that sentence is optional or outright unnecessary.

1648688817.png (242.4 KB, 650x403, 1E7384336DB2819FB5C4CBC1E607462C-248240.png)

>>339992

>I'm a bit curious what gave you that impression? Was it my latest "story" (even if it was more like an action scene without context)?

Your latest job is one such example, but i think you've had the touch since that earlier Revengeful-Shim greentext of the previous bread. which is kind of the greentext that got me started on Rainmetall. Yeah, you can either feel pride or cringe now

>>339988

>>339989

Ironic, given the fact I only started trying to learn english because the political discourse 'round here is 90% non-sense, and the rest good old mexican banter.

>I'm a bit curious what gave you that impression? Was it my latest "story" (even if it was more like an action scene without context)?

Your latest job is one such example, but i think you've had the touch since that earlier Revengeful-Shim greentext of the previous bread. which is kind of the greentext that got me started on Rainmetall. Yeah, you can either feel pride or cringe now

>>339988

>>339989

Ironic, given the fact I only started trying to learn english because the political discourse 'round here is 90% non-sense, and the rest good old mexican banter.

>>340005

Well, then I feel proud.

I think Rainmetall is cool in concept, the formatting problems were the real problems. I have so far, then again, I haven't actually read your whole story, no problems with the plot of your story. It's good.

I wrote that piece because, while I never picked out an official best pony, I have obsessed over Sunset the most. Read endless series of fanfics on her and thought about writing stories about her myself. I especially like to think about the possibility of her and Cadance studying under Celestia at the same time. I can't help but wonder what kind of relationship the pair could have had.

Ooh, I just noticed that pic of a pillow-throwing Sunset is what I had attached in with that story.

Well, then I feel proud.

I think Rainmetall is cool in concept, the formatting problems were the real problems. I have so far, then again, I haven't actually read your whole story, no problems with the plot of your story. It's good.

I wrote that piece because, while I never picked out an official best pony, I have obsessed over Sunset the most. Read endless series of fanfics on her and thought about writing stories about her myself. I especially like to think about the possibility of her and Cadance studying under Celestia at the same time. I can't help but wonder what kind of relationship the pair could have had.

Ooh, I just noticed that pic of a pillow-throwing Sunset is what I had attached in with that story.

Is he right? Is this what makes the women in Arcane so well-written, or is he just talking out of his ass?

[YouTube] How ARCANE Writes Women![]()

[YouTube] How ARCANE Writes Women

>>340063

Thanks bro I was using KissAnime and a Kickass Torrents proxy to watch Arcane

I am NEVER giving netflix money

Thanks bro I was using KissAnime and a Kickass Torrents proxy to watch Arcane

I am NEVER giving netflix money

>>340017

>Well, then I feel proud.

>I think Rainmetall is cool in concept

Thanks, glad you feel that way.

>I haven't actually read your whole story

Don't worry, I struggle to fully read a fic unless am absolutely engaged with it.

>I wrote that piece because, while I never picked out an official best pony, I have obsessed over Sunset the most.

It was easy to figure that one out, waifu or not.

>I especially like to think about the possibility of her and Cadance studying under Celestia at the same time.

I remember you suggested the prompt before. It's a pretty neat idea. You can tell that's why Cadence is on Rainmetall

>I just noticed that pic of a pillow-throwing Sunset is what I had attached in with that story

Exactly.

Just keep workin' on it!

>Well, then I feel proud.

>I think Rainmetall is cool in concept

Thanks, glad you feel that way.

>I haven't actually read your whole story

Don't worry, I struggle to fully read a fic unless am absolutely engaged with it.

>I wrote that piece because, while I never picked out an official best pony, I have obsessed over Sunset the most.

It was easy to figure that one out, waifu or not.

>I especially like to think about the possibility of her and Cadance studying under Celestia at the same time.

I remember you suggested the prompt before. It's a pretty neat idea. You can tell that's why Cadence is on Rainmetall

>I just noticed that pic of a pillow-throwing Sunset is what I had attached in with that story

Exactly.

Just keep workin' on it!

Do you think Fallout Equestria: Lionheart tries too hard to be adult in an inauthentic way?

At the time making the hero a male prostitute seemed like a good metaphor for how society fucks him.

But the hook with Twilight dragged people into an exciting chase with a character they already care for: Twilight Sparkle.

The audience has less reason than usual to care about OCs because this is not a new piece of media they suspended their disbelief for, this is fanfiction and they come into it with expectations they feel entitled to have fulfilled. Making the main heroine a literal clone of Twilight wasn't enough, I should have written an elderly Twilight on her deathbed sending a message through time to her past self to warn her of the future and get a young idealistic hopeful Twilight Sparkle who did nothing wrong to try and clean up every last mistake in Fallout Equestria.

Or divorced it entirely from FE and FIM so a story about humans being oppressed by libtards doesnt have to tie into nuclear pony retardity.

At the time making the hero a male prostitute seemed like a good metaphor for how society fucks him.

But the hook with Twilight dragged people into an exciting chase with a character they already care for: Twilight Sparkle.

The audience has less reason than usual to care about OCs because this is not a new piece of media they suspended their disbelief for, this is fanfiction and they come into it with expectations they feel entitled to have fulfilled. Making the main heroine a literal clone of Twilight wasn't enough, I should have written an elderly Twilight on her deathbed sending a message through time to her past self to warn her of the future and get a young idealistic hopeful Twilight Sparkle who did nothing wrong to try and clean up every last mistake in Fallout Equestria.

Or divorced it entirely from FE and FIM so a story about humans being oppressed by libtards doesnt have to tie into nuclear pony retardity.

>>341000

Legit criticism. It isnt that FoE:l tries too hard [...] its that all of your writing does. For instance, you simply cannot do 'subtlety' and yet you write as though you dont expect the reader to get that you were trying to be subtle.

For example, the method you use to apply 'flaws' to characters is basic. You dont include flaws because you want the character(s) to grow/develop, you include them because you have read/been-told that the characters are supposed to have flaws to overcome over the course of the story, but complicated flaws and development are really hard to write, so your mom lol. There is the faintest starlight glimmer of recognition of what MIGHT be a better storyline, but at the climax of execution you regularly resort to cheap tropes and out-of-context and/or irrelevant (read: lazy) memes and jokes that convey a subtle message of "I cant be arsed, because you're simply not worth the effort to do a better job".

Thats how your writing comes across.

And before you ask, no I DONT care to figure out what would be 'better', thats like asking what sound would be better than nails on a chalkboard; 'please god anything but more of that' is the general sentiment, though Im speaking purely from my experience.

Legit criticism. It isnt that FoE:l tries too hard [...] its that all of your writing does. For instance, you simply cannot do 'subtlety' and yet you write as though you dont expect the reader to get that you were trying to be subtle.

For example, the method you use to apply 'flaws' to characters is basic. You dont include flaws because you want the character(s) to grow/develop, you include them because you have read/been-told that the characters are supposed to have flaws to overcome over the course of the story, but complicated flaws and development are really hard to write, so your mom lol. There is the faintest starlight glimmer of recognition of what MIGHT be a better storyline, but at the climax of execution you regularly resort to cheap tropes and out-of-context and/or irrelevant (read: lazy) memes and jokes that convey a subtle message of "I cant be arsed, because you're simply not worth the effort to do a better job".

Thats how your writing comes across.

And before you ask, no I DONT care to figure out what would be 'better', thats like asking what sound would be better than nails on a chalkboard; 'please god anything but more of that' is the general sentiment, though Im speaking purely from my experience.

>>341000

I agree with most of what he [ >>341025 ] says, I'm only hesitant on some stuff.

I'd say you're making the same flaw as Disney made for the Star Wars sequels: Focusing on fan service.

Yes, bronies like already established characters from fim but it's not like there is no market for ocs in the community. On another note but with a thin connection, you want to use Twilight to bait bronies into reading your story. This is the impression I get, anyway. There are two problems with this: You assume that after you hooked the bronies into your story, they will obviously like the none-Twilight parts of your story. The second thing, which is admittedly kinda cute, is that you think that Twilight just being in a story is enough for the bronies to read it. While people have faves and are more likely to read a story with them included, it's still only half the puzzle. The second part is to have something to combine the character with, like a premise.

I got an epiphany about my own issues today and it fits kinda with what your problem is. I'd advise focusing less on the appeal of your stories and more on not having flaws in whatever you write. So

I agree with most of what he [ >>341025 ] says, I'm only hesitant on some stuff.

I'd say you're making the same flaw as Disney made for the Star Wars sequels: Focusing on fan service.

Yes, bronies like already established characters from fim but it's not like there is no market for ocs in the community. On another note but with a thin connection, you want to use Twilight to bait bronies into reading your story. This is the impression I get, anyway. There are two problems with this: You assume that after you hooked the bronies into your story, they will obviously like the none-Twilight parts of your story. The second thing, which is admittedly kinda cute, is that you think that Twilight just being in a story is enough for the bronies to read it. While people have faves and are more likely to read a story with them included, it's still only half the puzzle. The second part is to have something to combine the character with, like a premise.

I got an epiphany about my own issues today and it fits kinda with what your problem is. I'd advise focusing less on the appeal of your stories and more on not having flaws in whatever you write. So

>>341049

Not only was Twilight in the story at first, she was running from rapists. For the sake of those with no idea who raiders are they announced "we are going to rape you" but I think I spelled that out too much for those who already know. I could have written her thinking "those sons of bitches got fluttershy" but that would turn away fluttershy fans. Anyway it was a great hook right until an overpowered guy showed up as a joke and they talked too much and I mocked Fallouts gameplay contrivances turned up to 11 in FE one too many times. I think that part ruined the hook. Suddenly Twilight was just a character in a book inside the book and that is too meta. Suddenly the story focuses on the writer of the book and how society fucks him but people just wanted to see Twilight find a healing potion for her horn and magically obliterate all rapists on her way to the designated chosen one destination.

>>341025

Having a low charisma character in Fallout is good for the meta because it means more points for more useful stats. I wasn't sure how else to show his poor social skills but saying your mom to a grieving man and making "i have to take a shit, bye" his idea of sweet talking his way out of a situation seemed like a good way to display that.