http://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1500598;jsessionid=50B6B7F230FD91DE5A1502AB6840B455

Sanger, Margaret (14 September 1879–06 September 1966), birth control advocate, was born Margaret Higgins in Corning, New York, to Michael Hennessey Higgins, an Irish-born free thinker who eked out a meager living as a stonemason, and Anne Purcell Higgins, a hard-working, devoutly Roman Catholic Irish-American. Deeply influenced by her father’s iconoclasm, Margaret, one of eleven children, was also haunted by her mother’s premature death, which she attributed to the rigors of frequent childbirth and poverty. Determined to escape a similar fate, Margaret Higgins, supported by her two older sisters, attended Claverack College and Hudson River Institute before enrolling in White Plains Hospital as a nurse probationer in 1900. She was a practical nurse in the women’s ward working toward her registered nursing degree when her 1902 marriage to architect William Sanger ended her formal training. Though plagued by a recurring tubercular condition, she bore three children and settled down to a quiet life in Westchester, New York. In 1911, however, in an effort to salvage their troubled marriage, the Sangers abandoned the suburbs for a new life in New York City.

The radical activism and bohemian culture that permeated New York in the prewar years created a formative educational environment for Margaret Sanger. “Our living-room,” she recalled in her autobiography, “became a gathering place where liberals, anarchists, socialists and IWW’s could meet.” Exposed to modernist notions of political, social, and personal revolution, Sanger discovered the ideological justifications and practical outlets for her rebelliousness and unconventionality. She joined the Women’s Committee of the New York Socialist party and participated in several labor actions undertaken by the Industrial Workers of the World, including the notable 1912 strike of textile workers at Lawrence, Massachusetts. Sanger’s emerging feminist/Socialist interests, coupled with her nursing background, led in 1912 to an invitation to write “What Every Girl Should Know,” a column on female sexuality and social hygiene for the New York Call. The series quickly drew the attention of postal authorities, which in 1913 banned her article on venereal disease as obscene.

Sanger’s general interest in sex education and women’s health soon focused on family limitation. Returning to work as a visiting nurse among the immigrants of New York City’s Lower East Side, she saw graphic examples of the toll taken by frequent childbirth, miscarriage, and self-induced abortion. With access to contraceptive information prohibited on grounds of obscenity by the 1873 federal Comstock law and a host of state laws, Sanger realized that poor women did not have the same freedom from the physical hardships, fear, and dependency inherent in unwanted pregnancy as did those radical middle-class women who were espousing sexual liberation. Awakened to the connection between contraception and working-class empowerment by anarchist/feminist Emma Goldman, Sanger became convinced that liberating women from the risk of unwanted pregnancy would effect fundamental social change. With older feminists espousing family limitation through sexual abstinence and Socialists unwilling to be distracted by a fight for birth control, Sanger launched her own campaign, challenging governmental censorship of contraceptive information by embarking on a series of law-defying confrontational actions designed to force birth control into the center of public debate.

In March 1914 Sanger began publishing The Woman Rebel, a radical feminist monthly that advocated militant action and the right of every woman to be “absolute mistress of her own body.” The educational, economic, and political equality espoused by most feminists were irrelevant, Sanger declared, unless women first had the means to avoid the burden of unwanted pregnancies. Only birth control, a term coined in The Woman Rebel, would free women from the tyranny of uncontrolled childbirth. Although she did little more than espouse birth control in The Woman Rebel, postal authorities suppressed five of its seven issues. Sanger defied the authorities by continuing publication while preparing her next salvo against the obscenity laws: Family Limitation, a sixteen-page pamphlet containing the most precise evaluations and graphic descriptions of various contraceptive methods then available to American women. In August 1914 Margaret Sanger was indicted for violating postal obscenity laws in The Woman Rebel. Unwilling to risk imprisonment, she jumped bail in October and, using the alias “Bertha Watson,” set sail for England via Canada. En route she ordered the release of Family Limitation. A few weeks later William Sanger was tricked into providing a copy of the pamphlet to an operative of antivice crusader Anthony Comstock and went to jail for thirty days. This escalated interest in birth control as a civil liberties issue.

…

end quote.

Which has priority? The individual or the community?

Every solution is the next problem in a closed system.

/mlpol/ - My Little Politics

Archived thread

>>111476

Yes. While contraception could lead to more promiscuity, having fewer children born from couples unable to properly care for them is ultimately beneficial to society.

Yes. While contraception could lead to more promiscuity, having fewer children born from couples unable to properly care for them is ultimately beneficial to society.

>>111478

But the very poor can't afford contraception. Worse in poor countries children are a needed labor and pension plan, even more important, when child mortality is high, they will have more children to route around those deaths. In contrast the rich functional societies stop having children so they can play more vidya.

But the very poor can't afford contraception. Worse in poor countries children are a needed labor and pension plan, even more important, when child mortality is high, they will have more children to route around those deaths. In contrast the rich functional societies stop having children so they can play more vidya.

Planned Parenthood gives contraception to poor white people. It also gives misinformation to poor white people about how DANGEROUS and RISKY and PAINFUL and POTENTIALLY FATAL having children can be. It encourages women of childbearing age to slut around instead of settling down and having kids. It encourages women to have sex with no strings attached, no emotional bonds or real relationships or dopamine.

Meanwhile, the same liberal billionaires that fund Planned Parenthood and ensure it gets government funding as a "Charitable Organization" fund "Pograms" that pay black women for each kid they have.

Contraception is good, but it's used as a stick to beat conservatives with for finding the left's excessive abortion morally distasteful.

Meanwhile, the same liberal billionaires that fund Planned Parenthood and ensure it gets government funding as a "Charitable Organization" fund "Pograms" that pay black women for each kid they have.

Contraception is good, but it's used as a stick to beat conservatives with for finding the left's excessive abortion morally distasteful.

>>111484

> the very poor can't afford contraception

The very poor want a lot of children so they can get gibs from goverment, chidren are also a tool for survival in very poor places.

Also, contraception is as easy as a punch in the stomach too, so there's that.

Really, i don't think this will have any impact on society, maybe some more children will be born but don't expect a meaningful impact.

> the very poor can't afford contraception

The very poor want a lot of children so they can get gibs from goverment, chidren are also a tool for survival in very poor places.

Also, contraception is as easy as a punch in the stomach too, so there's that.

Really, i don't think this will have any impact on society, maybe some more children will be born but don't expect a meaningful impact.

>>111494

>Meanwhile, the same liberal billionaires that fund Planned Parenthood and ensure it gets government funding as a "Charitable Organization" fund "Pograms" that pay black women for each kid they have.

I'm completely opposed to this shit. The taxpayer should not be footing the bill for these nigglets. If you're going to breed, then start a family. The government shouldn't be replacing the father in the family. We should be gutting welfare and supporting the family unit again.

>Meanwhile, the same liberal billionaires that fund Planned Parenthood and ensure it gets government funding as a "Charitable Organization" fund "Pograms" that pay black women for each kid they have.

I'm completely opposed to this shit. The taxpayer should not be footing the bill for these nigglets. If you're going to breed, then start a family. The government shouldn't be replacing the father in the family. We should be gutting welfare and supporting the family unit again.

>>111476

While contraception has its clear and obvious uses, people cannot be trusted to use them for the right reasons. Current dating culture in the west being the biggest, most flamboyant, most heinous misuse of contraception and abortion out there, while use in an established marriage between two partners expressing their love for one another through sexual intercourse without having to worry about conceiving represents the moral use.

So yes I suppose, but for the right reasons, but surprise surprise you can't trust people with their own freedom. The worst people are always gonna drag down the best people to be just as debased and soulless as them. We live in a free society, the major fault with this is that it invites problems like these with no real way to deal with them in totality without infringing that freedom.

While contraception has its clear and obvious uses, people cannot be trusted to use them for the right reasons. Current dating culture in the west being the biggest, most flamboyant, most heinous misuse of contraception and abortion out there, while use in an established marriage between two partners expressing their love for one another through sexual intercourse without having to worry about conceiving represents the moral use.

So yes I suppose, but for the right reasons, but surprise surprise you can't trust people with their own freedom. The worst people are always gonna drag down the best people to be just as debased and soulless as them. We live in a free society, the major fault with this is that it invites problems like these with no real way to deal with them in totality without infringing that freedom.

Which is more important.. freedom or culture?

>>111476

>Which has priority? The individual or the community?

Its a balancing act that depends on the external forces and internal ones. When the people are good and the world is stable then a justice leader should give them anarchy for their loyal services.

But when the people degenerate or the nation's sovereignty is questioned then a good leader will strip the people of their anarchy in an attempt to fix the problem.

The only way we can fix what has happened today is if we either have a leader who is willing to execute (((those))) in academia and the media and then establish a military backed monarchy to ensure this never happens again. That or the day of the rope where we execute (((them))) ourselves.

>>111519

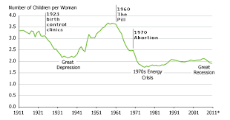

Can't read an image made for ants.

>Which has priority? The individual or the community?

Its a balancing act that depends on the external forces and internal ones. When the people are good and the world is stable then a justice leader should give them anarchy for their loyal services.

But when the people degenerate or the nation's sovereignty is questioned then a good leader will strip the people of their anarchy in an attempt to fix the problem.

The only way we can fix what has happened today is if we either have a leader who is willing to execute (((those))) in academia and the media and then establish a military backed monarchy to ensure this never happens again. That or the day of the rope where we execute (((them))) ourselves.

>>111519

Can't read an image made for ants.

Contraception should begin and end with self restraint. Maybe a condom.

>>111476

no, women should be held responsible for their actions and decisions. It'll also put more pressure on people to get married if they want to have sex

no, women should be held responsible for their actions and decisions. It'll also put more pressure on people to get married if they want to have sex

18 replies | 10 files | 1 UUIDs | Archived

Ex: Type :littlepip: to add Littlepip

Ex: Type :littlepip: to add Littlepip  Ex: Type :eqg-rarity: to add EqG Rarity

Ex: Type :eqg-rarity: to add EqG Rarity